Temin’s path: A serene trail is dedicated to one of its remarkable users

Late afternoon sunlight backlights people biking and running along the Howard Temin Lakeshore Path in October 2010. Photo: Jeff Miller

To take the aesthetic measure of UW–Madison, one needs to know the Lakeshore Path. Perhaps no one knew this better than Howard Temin.

Each day that he worked in his McArdle laboratory, Temin would travel the familiar bike-pedestrian path, usually alone, tending, as one friend suggested, to his equilibrium and creativity. For the late Nobel Prize-winning scientist, the rustic, wooded path that skirts the shore of Lake Mendota was more than simply part of his morning commute; it was a bearing check for the human compass. Whether biking on a sun-kissed day or slogging on foot through the worst Wisconsin blizzard, the slight, boyish figure of the university’s most distinguished scientist was a reliable sight as he traversed the quiet lakeside path.

Today, in recognition of that symbiosis, and for his many contributions to the life of the university, the Lakeshore Path officially becomes the Howard M. Temin Lakeshore Path. At a late afternoon ceremony on the west end of the 1.6-mile path, friends and colleagues will gather to remember a remarkable scientist and human being, and to commemorate the path in his name.

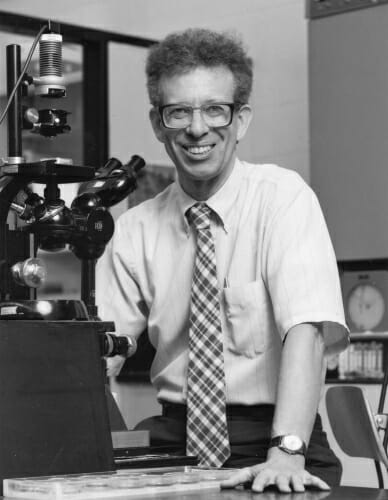

Howard Temin, a researcher at UW–Madison from 1960 until his death of cancer in 1994, is shown in 1986. His research focused on retroviruses and made important contributions to the treatment of cancer and HIV. Temin was awarded the Nobel Prize in 1975.

From the Limnology Lab on the east, where newly planted wild geraniums and wild ginger evoke a more pristine past, to the base of Picnic Point where migrating ducks raft on the swells of Lake Mendota’s University Bay, the Lakeshore Path is an insider’s highway through the heart of the university.

It was well known to Temin, and it became an integral part of his life. It may, in fact, have been one of the things that kept Howard Temin in Madison when stunning job offers trailed in the wake of his 1975 Nobel Prize in Medicine or Physiology.

“The path was very important to him,” said law professor Frank Tuerkheimer, an occasional biking companion and the faculty member who persisted in having the path named after the world-renowned biologist. “He recognized the value of having something like this at the center of the university.”

Once, a few years before Temin’s death from adenocarcinoma in 1994 at the age of 59, Tuerkheimer bumped into him on the Lakeshore Path, and Temin remarked that in the previous year he had walked the path every day but three.

“It wasn’t just a matter of going for a walk,” said Rayla Temin, Howard Temin’s wife and a UW–Madison professor of genetics. “It was the transition between home and work. It was a regular part of his life.”

For much of the year, the preferred form of transportation between Temin’s home and his campus laboratory was a bicycle. But when the Wisconsin winters set in, the bike would be put away and each morning, with a brisk, purposeful pace, Temin would set off on foot for campus.

“He walked in all kinds of weather,” said Rayla Temin. “He always said he liked the winter. It was a challenge to meet the elements. He found it invigorating.”

Those solitary walks were “an important time for him,” according to Roland Rueckert, an emeritus professor of molecular virology whose friendship with Temin spanned three decades. “It was the only quiet time he had. It was a way to get exercise and to think about what was going on in his life. With the Nobel, he got more attention than he wanted, so he needed that time.”

Although his commute along Lake Mendota afforded him rare moments of solitude and reflection, he never spurned company when a friend or colleague was encountered. Ever inquisitive, Temin had a knack for soaking up information from his companions. Said Tuerkheimer: “I would meet him periodically and we would talk. We had this deal. He’d ask me great questions about the law and I’d ask dumb questions about science.”

As stated on the two identical bronze plaques denoting the trail — set in boulders at each end of the path — Howard Temin was responsible for enlarging our understanding of how genetic information flows in cells. His discoveries, integral to our understanding of cancer, made it possible to find the AIDS virus and spawned techniques central to modern biotechnology.

And perhaps, just as genetic information traverses hidden pathways, so people follow the paths set before them. Howard Temin’s path in life was deliberate, forceful and, fortunately, ran along the shore of Lake Mendota.